Art Lessons

What can we extract from the abstract?

…in which we meander through art for a bit. We begin at the top of a gentle rise in a grassy meadow full of butterflies and grasshoppers, and look! There, by your foot! A shy little blue-tailed skink skitters into the weeds. For five minutes or so, let’s ponder the impact of art. Art can be very temporary or practically permanent, and it can make us more thoughtful. Here is a half-minute of silent video with which I can shamelessly manipulate your mind into being ready to consider art:

Jeff Koons’s giant chia pet of a sculpture, dubbed Split-Rocker, is one of the first works an arriving visitor will spy at the Glenstone Museum in Potomac, Maryland. Split-Rocker has a “skin” of carefully arranged, colorful flowering plants. The sculpture looks out at the world with two different half-faces. Why? You decide.

I strolled through the art at Glenstone recently with some friends and family. The museum’s layout encourages outdoor encounters with modern art as well as more traditional indoor, insulated, introspective encounters. Tickets are free but limited in number, so one books a tour weeks ahead, then hopes the weather gods smile upon the chosen day. We were fortunate. Our day was partly sunny and not terribly hot.

Premise for you, as a logic exercise: All art is modern art.

(If you’d like to invite my future posts into your email inbox, click “Subscribe now” and choose a free or paid subscription. Some posts at Thoughtful Enough are paywalled initially; others are free. This is one of the free ones. How could I put today’s post behind a paywall after telling you that Glenstone doesn’t charge for tickets? Thanks for reading. -JG)

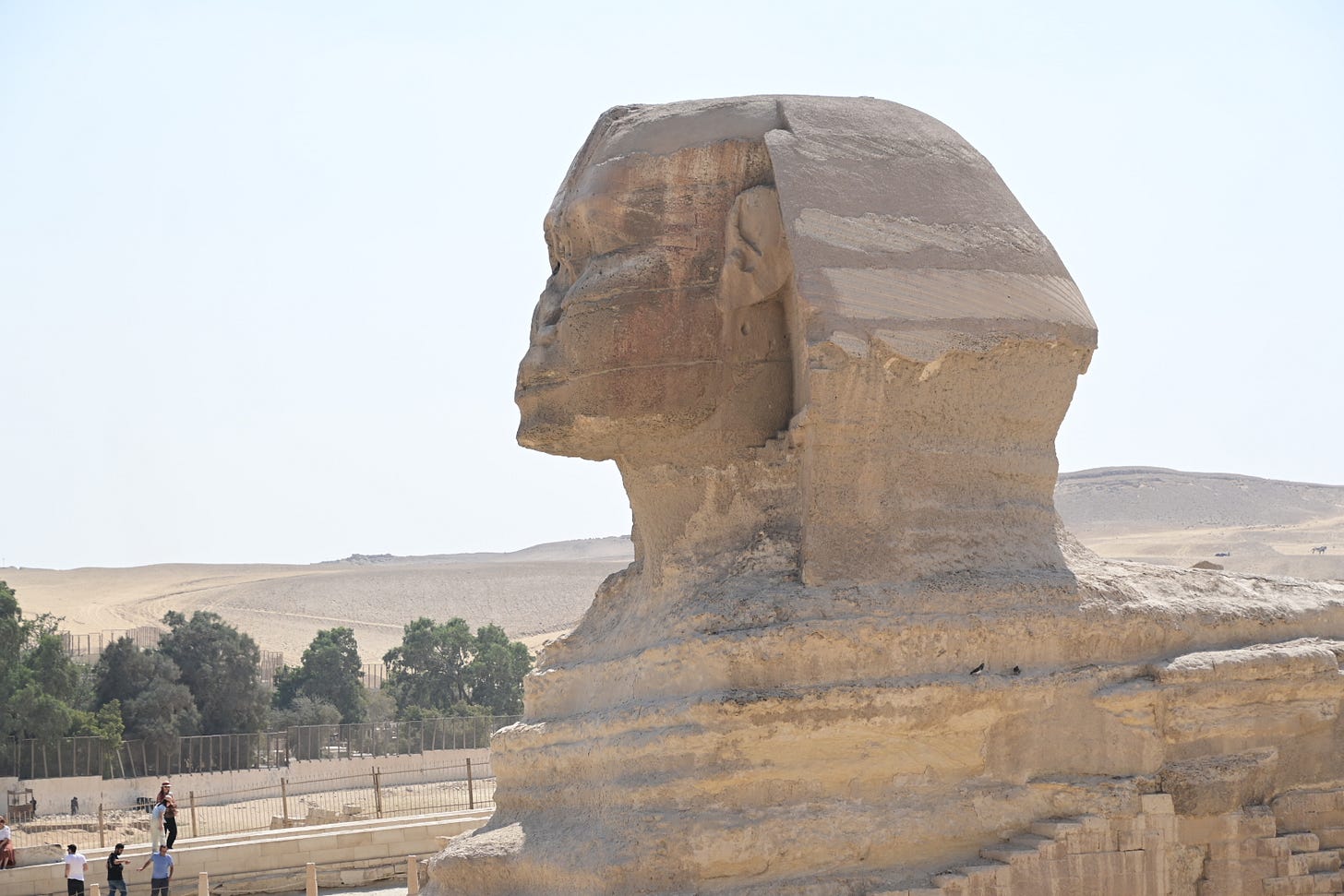

Here is modern art from about 4,600 years ago:

Sun, wind, and sand have left the Sphinx worse for wear, as has the spiteful behavior of people trying deface it (literally to de-face it). What is its meaning? Hypotheses have shifted like the sands around its base. A sun god. A pharaoh’s face. An intolerable heresy in the harsh desert haze. A mythological beast posing high-stakes riddles. The meaning of the Sphinx is fogged by the millennia. It’s blurry now.

Some art is blurry the moment it is created. Look how 19th century sculptor Rafaello Monti could sweet-talk a block of solid marble into becoming not just a Vestal priestess’s face, but also the gauzy veil obscuring that face.

Things get even more blurry in the 20th century’s dribbled enamel and oil paintings by Jackson Pollock, or in this dusky orange rectangle that Robert Motherwell topped with just a few linear strokes of smoky black:

If Motherwell’s abstract expressionism puzzles you, or if it annoys you as it annoys me, you might enjoy reading Kurt Vonnegut’s Bluebeard, a novel about an expressionist painter whose star shone brightly for a while. Like his fictional painter, author Vonnegut wrestles with the idea of art’s expiration date, its tendency to dissolve into shadow and be forgotten.

As you enjoy music or paintings or architecture by your favorite contemporary creators, you might wonder how long any given work will endure.

The Sphinx has endured! But of course there were other works that debuted 4,600 years ago and did not endure. I feel a pang of sympathy for the artist on the other bank of the Nile who sculpted a giant Sphanx, and the guy even farther to the east, in Nineveh, who wove a mighty Sphunx out of reeds from the banks of the Tigris. Sensational in their day. Long, long forgotten.

When we first meet art, our brains might assign meaning to it that the artist didn’t intend. Simone Leigh sculpted this tall female figure with an entwining snake as “Sentinel (Mami Wata),” drawing upon West African religious tradition.

My religious upbringing was different, so when I saw “Sentinel (Mami Wata)” at the Glenstone, my first thought was Eve in Eden encircled by Satan in his serpent guise.

Sometimes, artists use words as art. Jenny Holzer’s extensive exhibit at Glenstone sets words in motion along an electronic ticker tape, or etches words into metal, or carves words into marble, or enlarges words to fill a wall.

A memo from then-president George W. Bush establishes his belief, propped up by Justice Department interpretations, that the Geneva accords did not apply to Al Qaeda prisoners. As a couple pieces of 8.5” x 11” paper, the memo is a small thing. Enlarged by artist Holzer and silk screened onto linen to fill a wall, the words seem louder. Holzer’s art makes us consider: What does it say about us, what does it mean, to declare we are not obliged to treat our prisoners humanely?

In the next room we encounter a series of metal-leaf panels crafted by Holzer that seem blankly abstract… until we get close and notice words engraved across the upper portion of the panels. Each panel presents one text sent January 6, 2021, to or from the phone of White House chief of staff Mark Meadows. Here are people in President Donald Trump’s inner circle reacting to the riot at the U.S Capitol and to Trump’s silent, stubborn refusal to raise a finger to discourage that riot.

What could be smaller or more fleeting than a single sentence text? It perches in the palm of the hand. It is read in a heartbeat, and then with a mere thumb-swipe it scrolls from sight, unless someone engraves it into metal and hangs it on a wall.

Walt Whitman’s art of choice was poetry and he wrote, “I sound my barbaric yawp over the roofs of the world.” With that in mind, I’ll close with a concern and a wish. My concern is that “barbaric” is a more and more apt description of our national yawps. My wish: that you find some art upon which to reflect, or create some art of your own upon which others could reflect.